d: 1842

John Lynch

Summary

Name:

Nickname:

John DunleavyYears Active:

1836 - 1841Status:

ExecutedClass:

Serial KillerVictims:

10Method:

BludgeoningDeath:

April 22, 1842Nationality:

Australia

d: 1842

John Lynch

Summary: Serial Killer

Name:

John LynchNickname:

John DunleavyStatus:

ExecutedVictims:

10Method:

BludgeoningNationality:

AustraliaDeath:

April 22, 1842Years Active:

1836 - 1841bio

John Lynch was born around 1812 in County Cavan, Ireland, into a family that would experience the full weight of British colonial justice. At the age of 19, Lynch was convicted of obtaining goods under false pretenses during a trial in October 1831 and sentenced to transportation for life to the penal colony of New South Wales. He was transported alongside his father, Owen Lynch, who had received a seven-year sentence for possession of stolen goods. The two sailed from Dublin aboard the Dunvegan Castle, arriving in Sydney on October 16, 1832.

Lynch was initially assigned to work as a ploughman at 'Oldbury Farm' near Berrima in the Southern Highlands of New South Wales. The colonial convict assignment system saw men like Lynch effectively enslaved, working under harsh conditions. Life in these penal settlements was fraught with danger and brutality. His father died just two years into their sentence in 1834, leaving John in a foreign land with little support. While working at Oldbury, Lynch became entangled in bushranger-related violence and was accused of involvement in a robbery and the brutal murder of fellow convict Thomas Smith in 1836. Despite testimony from another convict implicating him, Lynch was acquitted.

murder story

In the years after his 1836 acquittal for the killing at Oldbury Farm, John Lynch’s life fell deeper into the harsh grind of penal servitude. Described by the Berrima correspondent to the Sydney Herald as having “been a long time in irons in different parts,” he spent part of that time laboring in a Newcastle stockade gang before emerging in Berrima in 1841.

One of the most telling episodes from his time in Newcastle was the infamous stabbing incident of 27 June 1839. Lynch reported that he was attacked in his hut by three inmate, Thomas Barry, Thomas Bolson, and Charles Wilson, who, evidently for retribution, bound his head in a blanket while one stabbed him in the chest. The three were tried in Sydney’s Supreme Court and sentenced to death, though their sentences were later commuted to transportation. Yet, in a chilling turn, Lynch confessed before his execution that he had staged the injuries himself to frame them, retribution disguised as victimhood.

By mid‑1841, Lynch had slipped free and returned to the familiarity of Berrima. He first visited his old contact, John Mulligan, expecting a payoff. Denied what he felt was owed, Lynch moved on to the Oldbury Estate, stealing eight bullocks and driving them toward Sydney. Fate brought him to Razorback Range, where he encountered a carrier, Edmund Ireland, and his young Aboriginal helper. In his confession, Lynch said he “began to form the plan of destroying the men, and possessing himself of the dray and property.” The next morning, he killed them both with tomahawk blows, buried the bodies in the bush, and pressed on with the stolen dray and team.

Having disposed of the goods, Lynch headed back with the dray, crossing paths with William Fraser and his son, who were driving a horse team. They camped together at Bargo Brush. During the night, a police constable questioned them about the missing dray, triggering terror in Lynch. Alone under the dray, he trembled until the constable left. By dawn, driven by desperation and greed, he killed both Frasers with swift tomahawk strikes, burying them under a spade’s weight, and lingered at the site until dusk fell.

It was a short run from this atrocity to the next. Lynch headed to Mulligan’s farm at Wombat Brush. On 18 August 1841, under the guise of collecting owed debts, he ingratiated himself with the family, offering rum while calmly planning his betrayal. That night, he lured the 18‑year‑old son out to fetch wood, and killed him with an axe swing. When suspicion grew, he murdered both parents and then horrifically raped and killed the 13‑year‑old Mary. He piled the bodies, set them aflame—with a haunting remark that they “burned as if they were so many bags of fat”—then buried the remains and burned their clothes.

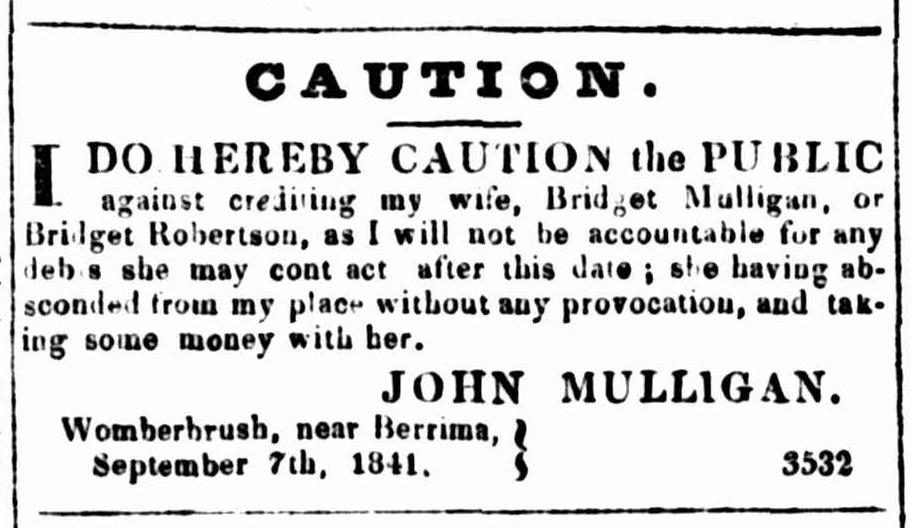

In a final act of deceit, Lynch placed a notice in the Sydney Gazette claiming that Mulligan’s wife had absconded, settling Mulligan’s debts in his name. He assumed the name John Dunleavy, brought in the unsuspecting Barnetts as laborers, and outwardly lived as the legitimate leaseholder. But neighbors pieced things together: bones were discovered, suspicions heightened, and investigations linked him to the multiple disappearances. By early 1842, authorities realized Lynch had confessed to a string of murders along the Berrima–Camden roads—and his fall from freedom was imminent.