d: 1867

John Clarke

Summary

Name:

Nickname:

Clarke Brothers / The Jingeras BushrangersYears Active:

1865 - 1867Status:

ExecutedClass:

MurdererVictims:

1+Method:

ShootingDeath:

June 25, 1867Nationality:

Australia

d: 1867

John Clarke

Summary: Murderer

Name:

John ClarkeNickname:

Clarke Brothers / The Jingeras BushrangersStatus:

ExecutedVictims:

1+Method:

ShootingNationality:

AustraliaDeath:

June 25, 1867Years Active:

1865 - 1867Date Convicted:

May 28, 1867bio

John Clarke was born around 1846 into a family steeped in hardship and criminality. His father, Jack Clarke, was a former convict sent to Australia aboard the Morley in 1828. After gaining his freedom, Jack settled in the Braidwood district of New South Wales where he married Mary Connell, and together they had five children.

Struggling to survive on a small leasehold in the harsh terrain of the Jingeras, Jack resorted to illegal activities like selling sly-grog (unlicensed alcohol) and cattle duffing—criminal trades he passed on to his sons, including John and his older brother Thomas. As boys, the Clarke brothers were raised in an environment of rebellion and resourcefulness, their view of property and justice shaped by a deep mistrust of colonial authority.

By their teenage years, John and Thomas were deeply involved in organized rural crime. Alongside their uncles Pat and Tom Connell, they mastered the arts of horse stealing and cattle rustling. Their group, known locally as the “Jerrabat Gully Rakers,” was notorious for their cunning use of bushcraft and their brutal efficiency. They were not simply outlaws—they were a rural gang built on survival, rebellion, and blood ties.

As gold fever swept New South Wales, the Clarke brothers saw opportunity. They shifted from livestock theft to bushranging—highway robberies, gold escort raids, and armed hold-ups. Their targets included publicans, farmers, storekeepers, and travelers.

murder story

From around late 1865 through April 1867, John Clarke and his brother Thomas led one of the most notorious bushranging gangs in southern New South Wales. Alongside a circle of relatives—including their uncles Pat and Tom Connell—and associates, the Clarke Gang was responsible for an estimated 71 robberies and hold-ups, and were implicated in the deaths of numerous individuals including police and civilians.

Operating across the gold-rich southern NSW, the gang roamed from Braidwood through the Jingeras toward the coast—reaching Bega, Moruya, and Nelligen. They ambushed gold shipments, seized mail coaches, and raided stores, farms, and inns with brutal regularity, running almost unchecked until late 1866.

In a particularly savage raid, the gang struck Nerrigundah. After ambushing passersby near Guelph Creek—wounding John Emmott with gunfire and beating others—they stormed the local store and tavern. They held 40 hostages, robbing and terrorizing them. When Constables Miles O’Grady and Smythe tried to intervene, a gunfight ensued: O’Grady was mortally wounded but managed to fatally shoot gang member William Fletcher before succumbing to his injuries. This violent encounter intensified the hunt for the Clarke Gang and eroded any lingering local sympathy.

Less than two months later, the Clarke Gang attacked the village of Michelago. They stole supplies from the general store and held residents at the inn while intoxicated themselves—drinking, brawling, and tormenting the locals—before finally releasing the captives after hours of chaos.

In early 1867, authorities dispatched a team of special constables—John Carroll, Patrick Kennagh, Eneas McDonnell, and John Phegan—to track down the gang. Near Jinden Station, the squad was ambushed, tied to trees, and executed. A blood‑soaked pound note was pinned to Carroll, a chilling taunt and warning to law enforcers. Historians believe the Clarke brothers were the masterminds, though they were never formally tried for these murders.

The brutality of these crimes prompted NSW to enact the Felons’ Apprehension Act (1866), allowing bushrangers to be declared outlaws and made liable to be shot on sight. Thomas Clarke was proclaimed an outlaw under the Act, signaling state‑sanctioned force against them.

By early 1867, many gang members were dead or captured. Patrick Connell, a key figure, was declared outlaw and killed in a shootout in July 1866. Another member, “Jemmy the Warrigal,” died from a skull injury around February 1867.

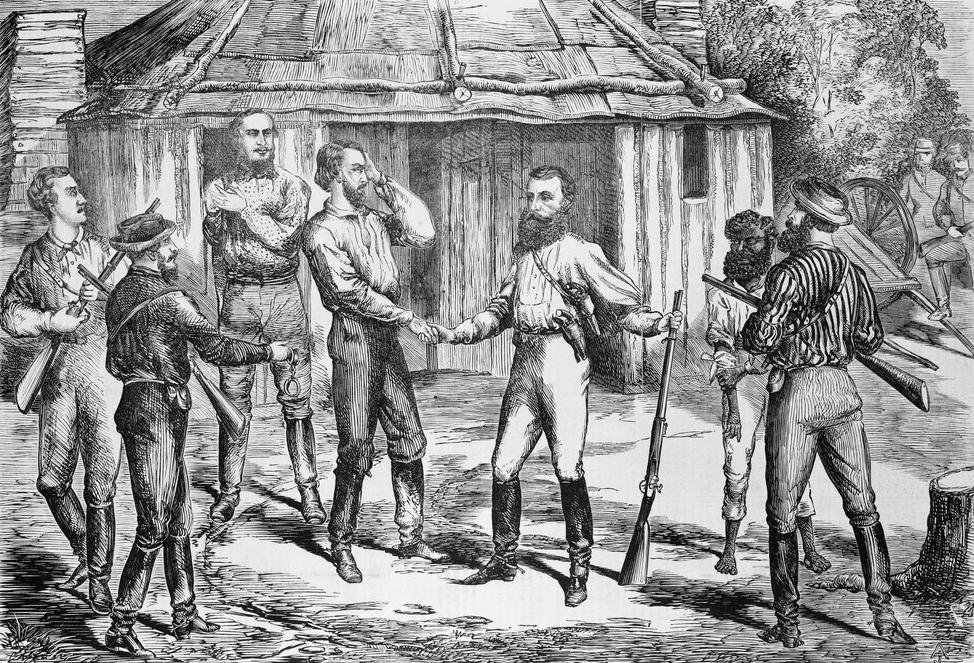

In late March, heavy floods devastated bush hideouts. The remains of accomplice Billy Scott were found on 9 April, reducing the gang to just Thomas and John Clarke. Acting on intelligence from a gang harbourer, police led by Senior Constable Wright and tracker Sir Watkin Wynne surrounded a hut at Jinden Creek (Berry’s Hut) on 26 April 1867. A fierce hours‑long gunfight erupted on 27 April. John Clarke was shot in the shoulder, Wynne sustained serious injuries (possibly requiring amputation), and Constable Walsh was wounded in the hip. Finally, the brothers surrendered—not with defiance, but with a handshake.

They were shackled and taken to Sydney after a committal hearing was held on 13 May 1867. Their trial on 28 May 1867 lasted just one day: Chief Justice Sir Alfred Stephen, a fervent anti‑bushranger figure involved in crafting the Felons’ Apprehension Act, presided. The jury took a mere 67 minutes to convict them—not even on murder charges, but attempted murder of Constable Walsh. Stephen stressed their execution was necessary for society’s peace, not vengeance.

On 25 June 1867, both John (aged about 21) and Thomas Clarke (about 27) were hanged on twin gallows at Darlinghurst Gaol.