1863 - 1922

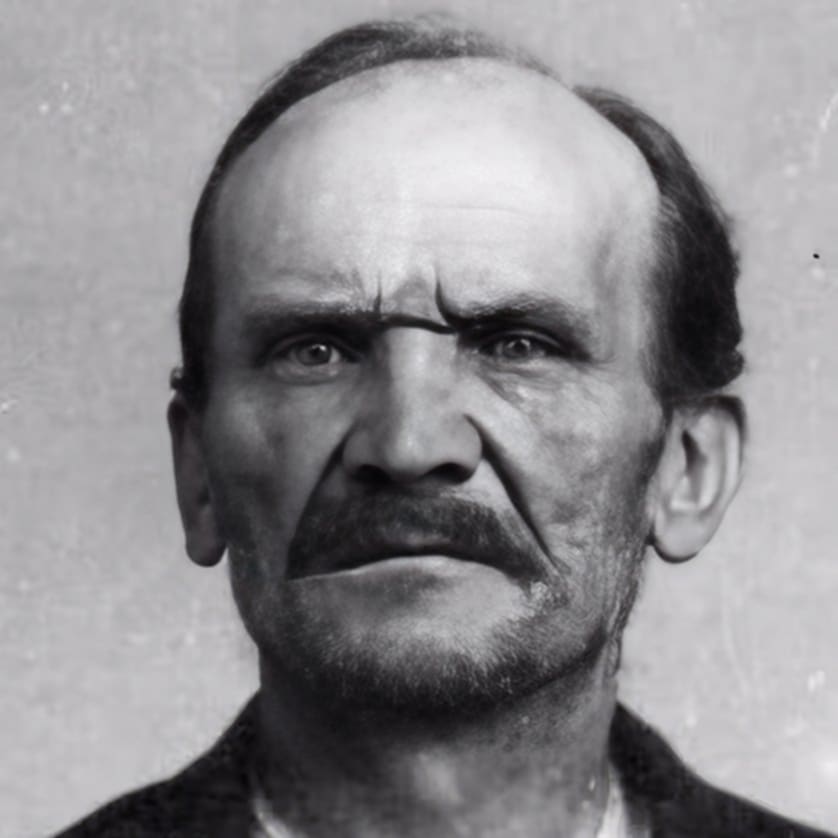

Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Großmann

Summary

Name:

Nickname:

The Berlin Butcher / Karl Grossmann / Beast of Silesian Train Station / Blue Beard of Berlin / Jack the RipperYears Active:

1918 - 1921Birth:

December 13, 1863Status:

DeceasedClass:

Serial KillerVictims:

26+Method:

UnknownDeath:

July 05, 1922Nationality:

Germany

1863 - 1922

Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Großmann

Summary: Serial Killer

Name:

Carl Friedrich Wilhelm GroßmannNickname:

The Berlin Butcher / Karl Grossmann / Beast of Silesian Train Station / Blue Beard of Berlin / Jack the RipperStatus:

DeceasedVictims:

26+Method:

UnknownNationality:

GermanyBirth:

December 13, 1863Death:

July 05, 1922Years Active:

1918 - 1921bio

Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Großmann was born on December 13, 1863, in Neuruppin, Kingdom of Prussia. Little is known about his early life, but it is recorded that he had troubling and sadistic tendencies.

Großmann grew up largely isolated, disliked for his unkempt appearance, poor hygiene, and unsettling behavior. His half‑brother Franz, one of the few family members he stayed close to, later described Karl’s early fascination with blood and animal slaughter. A childhood memory was that Karl was drinking warm pig’s blood directly from a slaughter wound. He was known to fixate on injured animals, watching them die with an intensity that alarmed other children. His peers often mocked him, while adults avoided him altogether.

During his early schooling, he helped tend the family’s goats in Treskow, where he earned the nickname “Zickenkarl” for smearing himself with salt to entice the animals to lick him. His behavior frequently blurred into cruelty, as he would smash heads with his billy goat in what he considered play. Academically, he struggled, leaving Volksschule after the third grade. Though he later claimed to have pursued further education, no records support this.

As a young man, he was involved in serious criminal activities that led to multiple convictions for child molestation. He was sentenced to 15 years in prison for fondling a ten-year-old girl and for the brutal rape of a four-year-old girl, who sadly died soon after the judgement.

After serving his time, Großmann's life took a different turn during World War I. He made a living by selling meat on the black market. Some locals claimed that he sold more than just regular meat. He also operated a hot dog stand near a train station close to his home. There were rumors that the meat he sold included remains of victims, as he reportedly disposed of bones and other inedible parts in the river nearby. These rumors grew when pieces of missing women were discovered in local canals, leading some to suspect that he had harmed many women and girls throughout his life.

murder story

Beginning no later than 1918, he used his location beside Berlin Ostbahnhof to select victims from among the thousands of migrant women arriving daily by train. Some were job‑seekers hoping to escape rural poverty; others were homeless or engaged in sex work. Großmann exploited both groups, luring them to his apartment with promises of employment as a housekeeper or by offering food, money, or shelter.

Police eventually estimated that the recovered remains represented at least 23 women, though some investigators believed the true total could have exceeded 50 or even 100. Meanwhile, neighbors regularly heard screams from Großmann’s apartment but dismissed them as rough sexual encounters.

Despite multiple reports from surviving victims, including teenagers and sex workers, police repeatedly failed to take action, often dismissing them due to prejudice against women involved in sex work or homelessness. One of the earliest missed opportunities occurred in March 1920 when a social worker discovered a 15‑year‑old girl in Großmann’s apartment and noted women’s clothing inconsistent with his claims about a deceased wife. Her requests for a search warrant were ignored.

By 1921, the brutality escalated. In early August, a homeless woman accepted his invitation for lodging and was tied up under the pretense of a “bondage fetish.” When she resisted, he beat her with a pestle and suffocated her. His landlord’s wife unexpectedly walked in on the scene, seeing the lifeless woman on the bed. Rather than alert police, she accepted money to remain silent. The victim, later identified as Elisabeth “Martha” Barthel, was dismembered after Großmann woke from a nap beside her body.

On 3 August 1921, he murdered Johanna Sosnowski, whose disappearance later prompted confrontation by her brother, a confrontation that temporarily resulted in Großmann’s brief arrest for assault but no investigation into the missing woman.

His final known victim was 34‑year‑old Marie Nitsche, an occasional sex worker from Dresden. Witnesses saw her accompany Großmann from Koppenstraße to a carnival on the night of 21 August 1921. A neighbor heard screams around 21:30 and insisted that her husband alert police. Officers forced entry into Großmann’s apartment and found him attempting suicide by drinking cyanide‑laced coffee. Nitsche lay nude on the bed, barely alive. She died seconds after discovery.

The arrest triggered a massive public outcry, with hundreds gathering outside the building. Survivors began coming forward, describing similar experiences of being tied, beaten, drugged, and raped. Some women recalled being given small gifts or money to gain their trust before violence began. Long‑time sex workers in the neighborhood admitted they had nicknamed him “Mysterious Karl,” warning newcomers to avoid him.

During interrogation, Großmann initially denied murder, claiming his victims had stolen from him. When police produced survivors whose description of his apartment matched the crime scenes, he shifted tactics. Detective Ludwig Werneburg finally obtained a partial confession by allowing Großmann supervised time with his beloved pet bird, Hänschen. Over several hours, he admitted to killing three women, Nitsche, “Martha,” and Sosnowski, and later acknowledged involvement in additional cases when confronted with physical evidence, such as personal belongings of missing women found in his apartment.

Despite these confessions, he refused to address the broader pattern of disappearances or the dozens of body parts recovered from the canals. Investigators believed he may have murdered women as often as once every few weeks, possibly more frequently, depending on opportunity.

His trial began on 3 July 1922, drawing intense press attention. Survivors attempted to attack him in court, and public outrage was so severe that he required protection from both the guards and the crowds. Though he retracted his confessions and insisted the deaths were accidental, the evidence against him was overwhelming.

Two days into the proceedings, on 5 July 1922, guards arrived at his cell to escort him to court and found him dead. He had fashioned a noose out of his bedsheet and hung himself from a doorframe nail. His suicide ended the trial, leaving many families without legal closure. The presiding judge formally announced the case closed, noting that Großmann had “turned himself in to a higher judge.”